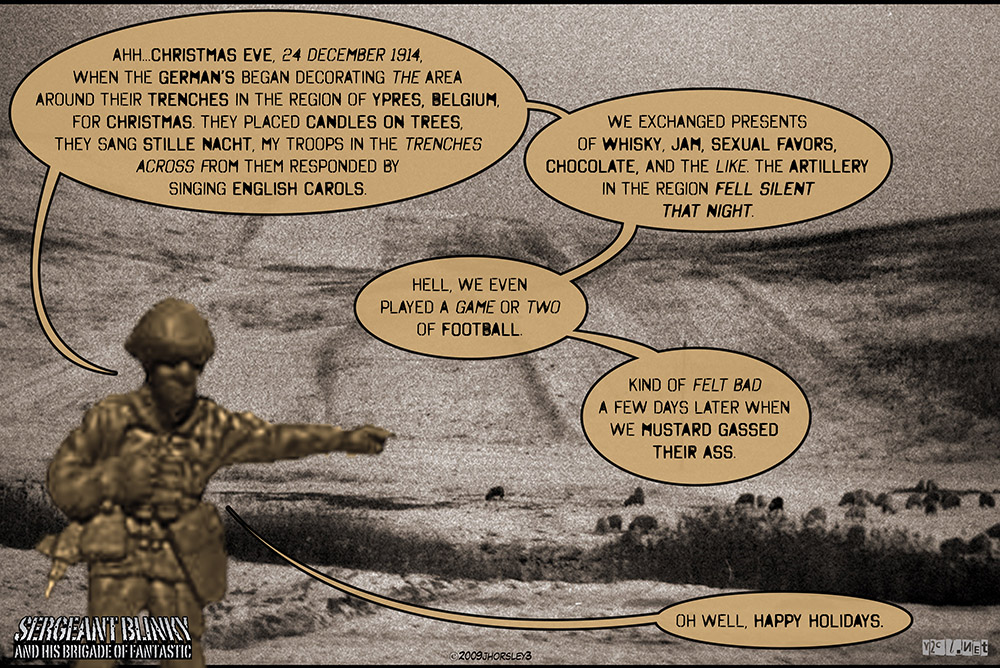

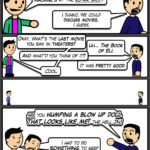

True story.

The truce began on Christmas Eve, 24 December 1914, when German troops began decorating the area around their trenches in the region of Ypres, Belgium, for Christmas. They began by placing candles on trees, then continued the celebration by singing Christmas carols, most notably Stille Nacht (Silent Night). The British troops in the trenches across from them responded by singing English carols.

The two sides continued by shouting Christmas greetings to each other. Soon thereafter, there were calls for visits across the “No Man’s Land” where small gifts were exchanged — whisky, jam, cigars, chocolate, and the like. The soldiers exchanged gifts, sometimes addresses, and drank together. The artillery in the region fell silent that night. The truce also allowed a breathing spell where recently-fallen soldiers could be brought back behind their lines by burial parties. Proper burials took place as soldiers from both sides mourned the dead together and paid their respects.

The truce spread to other areas of the lines, and there are many stories of football matches between the opposing forces.

In many sectors, the truce lasted through Christmas night, but in some areas, it continued until New Year’s Day.

The truce occurred in spite of opposition at higher levels of the military. Earlier in the autumn, Pope Benedict XV had begged for an official truce between the warring governments, “that the guns may fall silent at least upon the night the angels sang.” It was considered possible by the Germans but angrily denounced by the British who blithely ignored any further peace overtures made by Benedict – although the pope’s ten conditions for a lasting peace were largely subsumed by Woodrow Wilson in his “14 Points”.

British commanders Sir John French and Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien vowed that no such truce would be allowed again[citation needed], although both had left command before Christmas 1915. In all of the following years of the war, artillery bombardments were ordered on Christmas Eve to ensure that there were no further lulls in the combat. Troops were also rotated through various sectors of the front to prevent them from becoming overly familiar with the enemy. Despite those measures, there were a few friendly encounters between enemy soldiers, but on a much smaller scale than in 1914.